Thomas Heatherwick is on a mission.

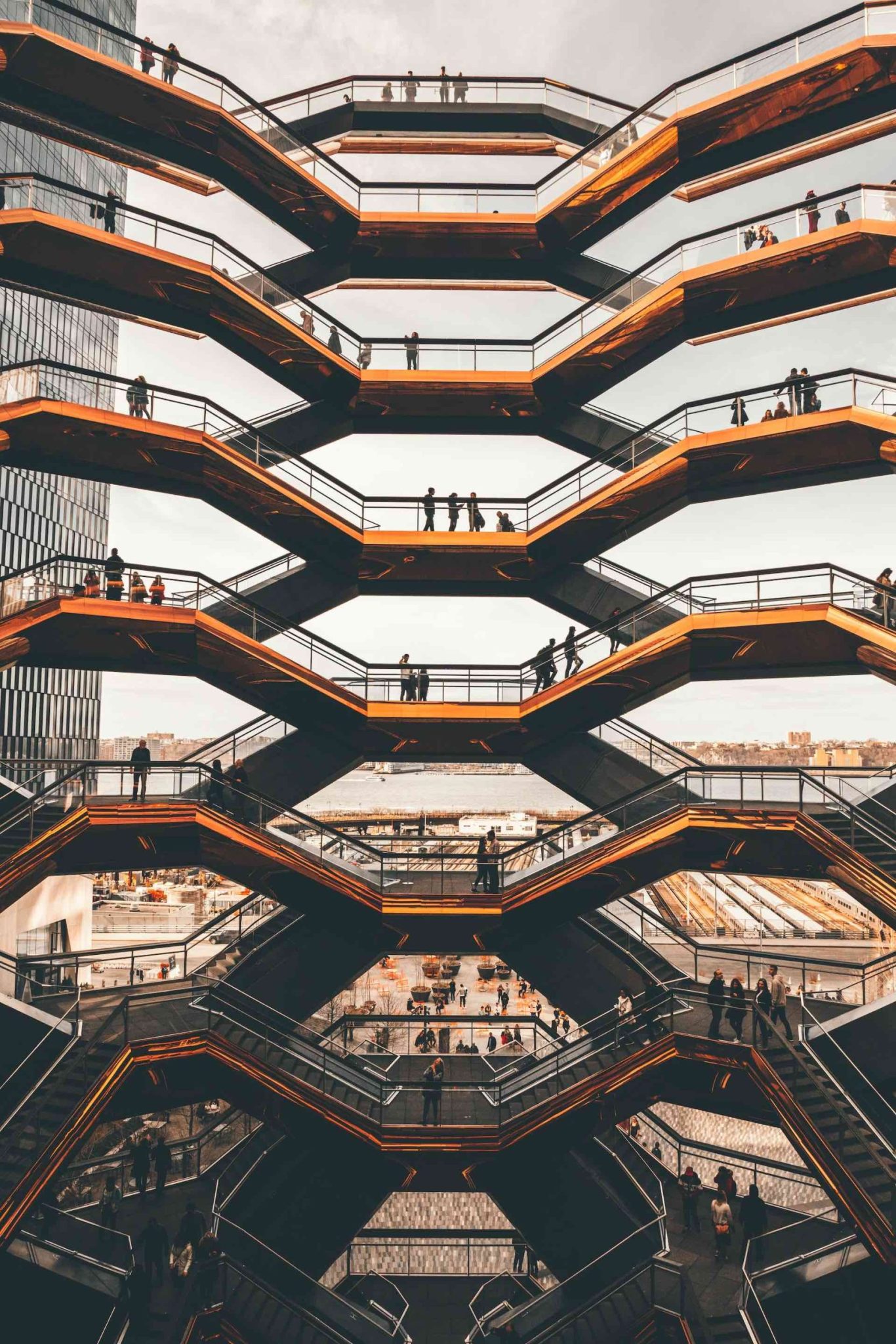

The British designer, famous for epic creations such as the Olympic cauldron for the 2012 Games, the Vessel at Hudson Yards in Manhattan, and Coal’s Drop Yard in Kings Cross, believes our towns and cities are suffering from an “epidemic of boringness.”

And so, this week, Heatherwick is launching a ten-year campaign for what he calls “radically human architecture.”

During a recent TED talk Heatherwick makes his case: “All over the world, humdrum designs built to poor briefs are being torn down, having lasted a matter of decades. Worse still, they are replaced by more of the same. Like endless photocopies with ever-fading ink, monotonous buildings blight our towns and cities – two dimensional and monolithic. Dull, flat, shiny and straight.”

“In the UK, 50,000 buildings are destroyed each year and the average life of a commercial building is only about 40 years.”

It is not hard to see Heatherwick’s point. At Hotfoot we are lucky enough to occupy a truly beautiful building.

The Storey, a Grade II listed building, was constructed in 1887 for “the promotion of art, science, literature, and technical instruction”.

The high ceilings, vast windows, grand corridors and architectural flourishes in the Jacobean Revival style make the heart soar.

But this is the exception, rather than the norm. All too often commercial buildings are bland and lifeless.

“There are ways we can reverse this. There’s a lot of thought going into different materials, greater efficiency, community engagement and carbon mitigation,” argues Heatherwick.

“But one crucial ingredient is missing: emotion. By which I mean the ability of buildings and places to mean something to us. To lift our spirits and connect us.

“The truth is, people only care for and adapt things that they love or value. And this applies to objects, buildings and places too.

“All over the UK, you can still find red phone boxes from the 1930s. Some are still payphones. But many more are coffee shops or mini-bookstores. People cherished them and found a way to preserve and reuse them, despite their function now having nothing to do with their form.

“We need to join up the dots between people’s emotional response to the things we design and the state of our planet.

“Let’s create buildings that are radically more human. Buildings that people love and adapt, not hate and demolish.”