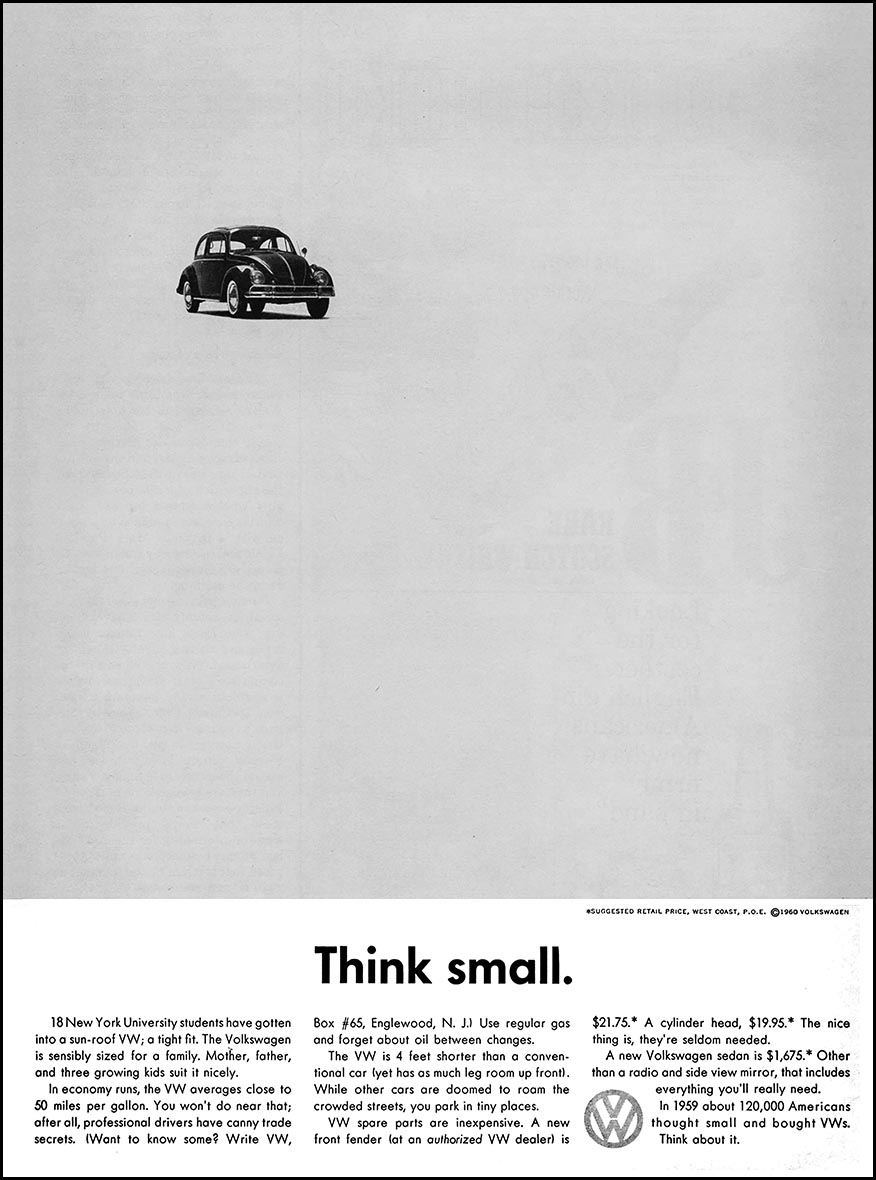

Think Small, one of the most famous ads in the advertising campaign for the Volkswagen Beetle in the US, art-directed by Helmut Krone and written by Julian Koenig at the Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB) agency in 1959. Source: Wikipedia / Fair use

How do you change someone’s mind?

If you ever engaged in a conversation about politics over dinner you will know from experience it is not easy.

You can throw facts, stats and personal testimony into the mix, but still your counterpart will remain stubbornly unmoved.

If anything, trying to change someone’s mind

can have the opposite to the intended effect. The more you try to persuade, the more they dig in.

This might be especially true of conspiracy theorists and those on either end of the political spectrum, but we can all be guilty of sticking to our talking points when our beliefs get challenged.

It is a common fallacy that people working in advertising are engaged in a constant battle to to persuade people to believe and do things against their will.

On the contrary, most potential customers already know what they want. The role of the advertiser, in most cases, is to guide them to a specific outcome.

You cannot, after all, very easily persuade someone they are thirsty if they are not.

But you might be able to encourage them to choose your particular brand of soda over another when they are ready to quench their thirst.

This is not to say advertising never attempts to dramatically shift opinions.

When the Volkswagen Group bought the Czech car manufacturer Skoda they did a fantastic job of shifting perceptions of the brand.

Decades earlier VW did a similar trick with the Beetle, which they successfully sold into the American market despite its tiny size and the fact it had first been commissioned by Hitler (just imagine getting that creative brief on your desk).

Dove’s Campaign for Real Beauty did something arguably more significant by attempting to change the way people think about body image. Rather than use airbrushed professional models, as was the norm, they chose people that were more relatably… normal.

But when it comes to politics and belief systems it is much harder to change hearts and minds.

Emotion and appeals to reason both fall short when confronted with a fixed worldview with its own internal logic.

Which makes a recent podcast about the campaign to protect abortion rights by Marcela Mulholland and McKenzie Wilson all the more interesting.

Wilson suggested a bumper sticker that cleverly taps into libertarian themes to appeal to people that might otherwise support a ban: “Healthcare decisions are between a woman and her doctor – not Washington politicians.”